Frictional Lichenoid Dermatitis

AUTHORS:

Ryan Tetla • Donna Parker, MD • Stephanie Ryan, MD

AFFILIATIONS:

University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida

CITATION:

Tetla R, Parker D, Ryan S. Frictional lichenoid dermatitis. Consultant. Published online October 6, 2020. doi:10.25270/con.2020.10.00010

Received July 22, 2020. Accepted September 17, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Stephanie Ryan, MD, Assistant Professor, Division of General Pediatrics, University of Florida College of Medicine, 7046 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32608 (sfryan@ufl.edu)

A 5-year-old boy presented to urgent care with a pruritic rash present on his elbows and knees. The rash had been present for approximately 1 month and had no known etiology. The severity of pruritus had been keeping him awake at night. The parents had been treating the rash and associated pruritus with over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone but noted that it had had minimal effect. No one in the household other than the patient had a rash or pruritus. The patient’s family history was notable for a grandmother with eczema. Findings of a review of systems were normal.

Physical examination. On physical examination, the child was interactive and appeared healthy. He was normocephalic with moist, clear mucous membranes. His lungs were clear to auscultation without increased respiratory effort. His cardiovascular examination showed normal rate and regular rhythm without heart murmurs. His abdomen was soft, nondistended, and nontender to palpation.

Skin examination revealed flat-topped papules that were flesh-colored to slightly erythematous on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees (Figures 1 and 2). The skin between the papules was normal-appearing or slightly erythematous.

Figure 1. Flat-topped papules on the extensor surface of the patient’s right elbow.

Figure 2. Flat-topped papules on the extensor surface of the patient’s right knee.

The patient received a clinical diagnosis of frictional lichenoid dermatitis (FLD).

Treatment. No laboratory or imaging studies were performed. The patient’s parents were counseled that FLD is a benign and self-limiting condition. Given the history of difficulty sleeping due to the pruritus and the minimal effect of hydrocortisone, triamcinolone cream was prescribed to help minimize symptoms.

Discussion. FLD is a rarely diagnosed rash that occurs most commonly in children. It has been known by other names such as Sutton’s summer prurigo and dermatitis papulosa juvenilis, and previously it had been believed to be a variant of or have correlation with atopic dermatitis.1 The rash typically is described as flesh-colored or mildly erythematous flat-topped papules on the extensor surface of the elbows and knees, with unknown etiology to the patient and parents. FLD also has been reported to appear on the dorsum of the hands, the neck, and the cheeks.1,2 The pruritus of the rash is self-limiting, but if symptoms are concerning to parents or child, a mild topical corticosteroid can be prescribed for symptomatic control.2

FLD is associated with multiple seasonal recurrences for up to 5 years.1 Due to this seasonal recurrence in spring and summer, it previously had been hypothesized that the etiology can be attributed to friction, atopy, UV radiation, or a combination of the three.1-3 While UV irradiation did not cause papular eruptions in studies, some degree of photosensitivity is apparent.1

While biopsy is not required to make the diagnosis, hematoxylin-eosin–stained biopsy specimens would reveal nonspecific changes indicating orthokeratosis, preservation of the granular layer, epidermal hyperplasia with isolated areas of epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltration of CD3+ T cells, and upper dermis fibrosis.2,4

The authors of a 2015 cross-sectional analysis in India concluded that FLD shares no relationship with atopic dermatitis, attributing previous beliefs to misdiagnoses and to diagnostic criteria that lacked proper sensitivity and specificity.3 The same study also showed no evidence for the frictional etiology that had been previously believed.3 Nevertheless, the suspected etiology of UV radiation seems very likely, provided global seasonal occurrences are during the months with the highest UV indexes.3 Further studies could look to verify this correlation by evaluating the annual incidence of FLD and its relationship to annual UV indexes over several years, assuming proper diagnostic criteria.

A 2009 report described cases of FLD in 3 adult patients.4 While this disease has been seen most often in children since its first description in 1956, this 2009 case series would be the first reported diagnoses of FLD in adults.4 These 3 case diagnoses were verified through histologic comparison of biopsies. Much remains to be learned about FLD before the condition is fully understood.

REFERENCES:

- Menni S, Piccinno R, Baietta S, Pigatto P. Sutton’s summer prurigo: a morphologic variant of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987;4(3):205-208. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1987.tb00779.x

The Case: 11yo F presenting after an episode of altered mental status at home with normal exam but abnormal CT head.

Here’s how you answered the questions:

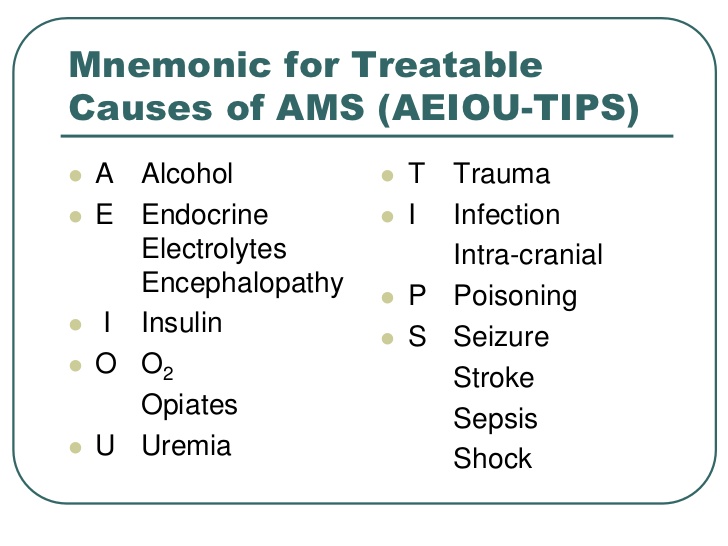

Discussion: The initial dilemma in this case lies in the fact that the patient had a concerning episode at home and then arrives asymptomatic with a normal exam. Faculty and fellows were somewhat split on discharging versus initiating a work up (most would start with head imaging). Dr. Rucker’s mnemonic of TIPS AEIOU (see below) is helpful in cases like this one to remind us of our ‘can’t miss’ diagnoses and decide if a work up is warranted.

Luckily (or unluckily, depending on your perspective) this patient is not discharged home and has an abnormal CT and recurrence of mild symptoms. The next step is not completely clear. Many fellows would consult Neurosurgery given the lack of clarity, while attendings would obtain vascular imaging. If imaging is obtained, the question becomes CTA/CTV (faster, easily accessible) or MRA/MRV (may delay, takes longer, patient needs to be cooperative however a better study if this patient is having a stroke).

Denouement: As patient was initially stable and without pain, decision was made to obtain MRI/MRA/MRV with and without contrast to facilitate diagnosis. As she was about to got to MRI, began to endorse mild headache, and imaging was changed to CTA to rule out continued unstable bleeding which would require emergent intervention.

CTA showed: There is a hemorrhagic lesion involving the left frontal lobe. There is a punctate focus of enhancement within it could represent a punctate focus of active bleeding for a small focus of early enhancement. Please see the report on the subsequently performed MRI for additional details.

And subsequent MRI studies showed:

1. There is a lesion in the left frontal lobe which has an appearance most consistent with a cavernous angioma. There are additional approximately 9 lesions in the supratentorial brain most consistent with additional cavernous angiomas.

2. Normal MRV of the head.

3. Normal MRA of the head.

Patient was admitted to the PICU and monitored. Started on Keppra for seizure prophylaxis. Neurosurgery deemed no intervention at this time. Discharged on HD#2.

Subsequent follow ups are re-assuring and neurosurgery will continue to monitor clinically.

The information in these cases has been changed to protect patient identity and confidentiality. The images are only provided for educational purposes and members agree not to download them, share them, or otherwise use them for any other purpose.

##############################

No comments:

Post a Comment